Shimon Minamikawa “GHOST, NEW PAINTINGS, TOKYO, etc.”

2011.1.16 Sun - 2.20 Sun

Opening reception : 1.16 Sun - SUNDAY BRUNCH 13:00 - 16:00

(Following the reception the gallery will remain open until 17:00)

MISAKO & ROSEN is pleased to announce our third solo exhibtion with artist Shimon Minamikawa. Minamikawa was born (1972) and presently lives and works in Tokyo, Japan. His work has been included in numerous exhibitions including, most recently, a solo presentation at the Roppongi Hills Art + Design Store in the Mori Art Tower, the exhibition celebrating the release of his debut artist book The ABC Book (published by Hikotaro Kanehira, 2010). In 2009, MISAKO & ROSEN presented Yokomichi Yonosuke, a series of 293 paintings created for Minamikawa’s collaboration with noted author Shuichi Yoshida. The pair’s project (Yoshida’s text generated in tandem with Minamikawa’s paintings) was published serially in the Mainichi Shinbun from April 2008 – March 2009.

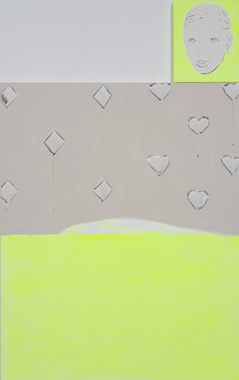

GHOST, NEW PAINTINGS, TOKYO, etc is representative of Minamikawa’s ongoing consideration of painting in relation to a lack of meaning-generation. More explicitly so than in past bodies of work, with the GHOST series, Minamikawa utilizes recent painterly tropes in a process of erasure equal to that of, say, a Rauschenberg to De Kooning – only in reverse. An additive, or representative process is contradictorily adopted to eliminate specific, particularly abstract painterly, significance. Referred to by Mori Art Museum Chief curator Mami Kataoka as spectra, Minamikawa’s paintings indeed do evoke through and as absence of anything but impression as history as painting; in the case of the Ghost paintings, Minamikawa’s focus is on a particularly present moment in painterly practice. Humor, generated from the naturally disjoint yet nonetheless linked -via serialized installation- canvases serves to temper the absence; yet, it humor born of nothing and this sobering thought lends Minamikawa’s new paintings a peculiar kind of weight.

The radiance of temporal spectra

Shimon Minamikawa’s (1972~) work shines like a spectra of mnemonic artifacts, resonating in the back of the brain, now projected onto canvas or paper: floating on the surface, only temporarily resident there. Minamikawa’s paintings, while technically part of a continuum of 20th century art’s technological and conceptual developments, simultaneously reflect a 21st century sensitivity, “learned from the urban environment”, and the mediated sensibilities of its pop music, television, and the internet. Indeed, the Shibuyas and Shinjukus of Tokyo overflow with transitory images flashing from neon lights and sign boards. Once awash in this busy cityscape, one’s own existence can come to feel amorphous, like the invisible man. Or, rather than seeing mnemonic spectra, perhaps it’s more accurate to say that Minamikawa breathes this contemporary urban world: He walks within in, as though inhaling these floating images, the city sounds, the chatting voices, the noises of cars and bikes, capturing portraits of the coded surface of the city, and then composes them onto canvas and paper as naturally as exhaling.

Minamikawa’s compositions often contain color planes, monochromatic traces of subtle brushwork, in geometrical patterns and figures, suggesting that the classical techniques of portraiture and abstract expressionism, color field painting and simulationism, each find a harmony, a common cipher, in memory. While his compositions of multiple canvases look like the neo-palimpsest layers of billboards you might see in front of Shibuya station, they might equally remind us of Jasper Johns’ (1930~) incorporation of urban motifs: the stripes on American flags, or “bull’s eye” targets depicted more like cross-hatchings or stepping stones or other such insignificant patterns on the street, seemingly beneath signification. Johns’ cross hatch and step stone paintings were exhibited as horizontally connected series, suggesting the form of Japanese folding screens. Later, they were merged with portraits and trompe l’oeil from his early career. Johns’ paintings introduced texture and materiality by using bee’s wax, in encaustic painting, to confront the flatness of signs within the 1950’s American urban culture, and the rise of the abstract expressionism, and making us reconsider the relationship between illusion and reality.

Another important reference when considering Minamikawa’s paintings is the 1980s /neo-geo/ work of Peter Halley (1953~). In Halley’s work geometric patterns function as a codification of industrialized society, such as depicted by Michel Foucault (1926~1984) in his book /Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison/, or Jean Baudrillard’s (1929~2007) /Hyperreality and Simulation/. His motifs in fluorescent paints, about cells and conduits, continue to translate theories about the real and the other, from the era which first saw the personal computer and video game, to we who live in the present day. Halley stated “I think geometry has become an important method for thinking about the structure/system of actual society, rather than merely as a field of art. Not only in the sense of framing redevelopment of cities or economic systems geometrically, but also in the fact that we take reality as geometric expression, and use geometry to represent reality” and “In post-modernism thinking, paintings are not relevant to current issues… (abbreviated) …because ours is the era of media.” Rather, Halley emphasizes the visceral nature of his depictions of post-industrial society in the materiality of the fluorescent paint he used, and the scale and spatiality of the frame.

In contrast, the meaning of creating the geometric patterns, the stripes and dots which appear again and again in Minamakawa’s paintings, can be read in how they indicate the technologies of reproduction. Here, the reproduced image, rather than being a concise copy of reality, hyper-real or simulated representation, actually functions as a signifier of temporal spectra: actuality, memory and virtual experience, coming and going. The veracity of Minamikawa’s geometric patterns has been stripped away, leaving only the remnants of brush strokes and paint drippings to exist as thin image veneers. It’s now some 20 years since the neo-minimalist simulationist artists. No probing questions about the uniqueness or originality of the image remain. There is nothing theoretically challenging about the precise reproduction. Ours is an era of editing, of re- contextualization, when anyone can put together existing photographs or images from the internet. The unbridled plagiarism of our age is equal in the frame with traditional Japanese aesthetics, such as the check patterns on sliding screen doors of the /Shokintei/ tea house in the Katsura Detached Palace, or the garden of the /Hojo/ (Abbot’s Hall) in Tofuku-ji Temple, designed by Mirei Shigemori, both in Kyoto, or the stripes on the /joshikimaku/, the tricolor curtain commonly used in Kabuki.

Minamikawa’s painting-as-spectra can also be seen in his figures. His portraits of evidently modern people are given a minimal treatment, like geometrical patterns. His models may be his friends, or people he’s seen on the street. It is irrelevant, because these are not portraits of their existences, but only encodings of their characters. They are thus shadowless and flat, transparent and white as ghosts, their facial expressions emotionless as a /noh/ (classical Japanese musical drama form) mask. Like momentary intrusions to one’s consciousness of passerby’s fashions or facial expressions, they are merely part of the spectra, not portraits in a traditional sense. They are paintings as spectra, momentary optical remnants on our retinas. This is why, despite the fluorescent colors and geometric patterns, they do not blare like the neon advertisements. They are temporal radiance, as realized by Minamikawa.

Mami Kataoka (Chief curator, Mori Art Museum, Tokyo)

Translated by David D’heilly