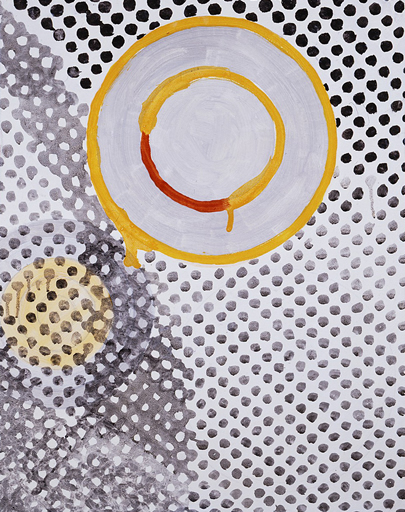

Shimon Minamikawa “Egypt, a woman of quality, circle and square”

December 18 mon- January 28 sun

closed from December 29 to January 8 for the winter holiday

opening reception December 18 17:00-21:00

Shimon Minamikawa was born (1972) and presently lives and works in Tokyo, Japan.

A student of the design department of Tama University of Art from 1991 to 1994, Minamikawa subsequently developed an interest in and eventual practice of fine art painting. Minamikawa received early recognition for his work – in 1999 he was selected as the first artist to exhibit as part of the Tokyo Opera City young artist exhibition program “Project N”.

The works by Minamikawa approach and express an adventurous stance towards the experience and abstraction of things present in the artist’s daily life. Unknown objects, observed yet distant people seen by Minamikawa are examined through the media of painting. Minamikawa has developed a unique style in which the influence of sources as diverse as master painting, historical abstract painting and pop are filtered throug the vocabulary of design in a means to develop a distinct visual vocabulary.

In the present exhibition, Minamikawa will present a new body of work including pyramid paintings which represent a recent development in his experimental approach towards abstraction. At once displays of spontaneity and highly controlled, the new paintings state a complex position in relation to the history of abstract painting.

Occasionally, we come across a work that we find difficult to say anything about. In Shimon Minamikawa’s case, this is always true. His works deftly escape our gaze’s efforts to describe and put into words any artistic style, and when in the end we think we have grasped the meaning, we’re back to scratch and the meaning has moved to a different context. This occurs even while we’re looking at a single painting of his, so it’s troublesome. His painting method and style are not varied. If anything, they are fixed, and no matter what motif he chooses, it’s within a believable range the painting has been done by the hand of one person. So, if we are to say what the problem is, it’s that his works usually have a sense of ambivalence. This ambivalence gives free rein to reference points and connectivity [in the painting], and the result is that each painting presents many different faces to the viewer. There are people who see his paintings and feel they have a slight retro feel. Then, recently there are those who say oppositely his paintings are drawn in a hip/cool fashion common currently, as well as even those who would see his paintings as examples of classic fine art traversing Formalism to American abstract expressionism. All of these are reactions to his paintings. More than anything else I feel there is contemporaneousness in this unconscious chameleon-like quality latent in Minamikawa’s works. Our experience with chameleon-like qualities is when we are engaged in thought, we are removed from the “constant context” each of us is accustomed to and thrust towards an unexpected context. Or, it is like a previously imperceptible existence becoming visible because of a change of perspective. It may be a slight exaggeration, but the Japanese expression “me kara uroko” (lifting the veil from one’s eyes) is a close approximation of this experience. In Minamikawa’s constantly changing and fluid works, while continuing to look at one of his paintings, it would not be unusual to experience something akin to continuously having the veil being lifted from one’s eyes.

We can see the model for the group of portraits in his new work in “14 Other Sides”, which he exhibited in his solo show in 1999. In 2002 without creating a series, per se, he generated a number of closely resembling compositions in which he tried multiple variations of a set of selected motifs such as the telephone, towel, and female portrait. In regards to distinguishing among those variations Minamikawa says, “I will continue to draw until meaning [of the subject] has been eradicated”. Using traditional categories such as portraits and still lifes, he intentionally eradicates not only the character and meaning of what should be the original subject/topic of expression in the motif, but also eradicates the painting’s center. When we look at a portrait, however, it is natural at first for thoughts to fix on the subject of the portrait. Yet, the face of that portrait, as we examine it through a succession of differences, dissolves, and gradually the individual parts become discrete elements that float precariously―the eyes, nose, mouth, the brow’s shape, position and direction, the presence or absence of the line that extends from the collar to the neck, the weight of the segment, the texture and viscosity of the hair’s pigment, and the verisimilitude of the background. Moreover, the touch of the brush, shape and angle of these features are combined in a way that they can’t be particularly integrated. By doing this and taking a fresh look, it’s understood that these asymmetrical elements are painted as a collage on one canvas from a perspective like compound eyes as in Cubism. His big tableaux are similar―the difference being the mix of several elements into one painting, which causes the central support to waver, or he splits the elements into several works and thereby causes a loss of meaning. Minamikawa deals with representational imagery. But more than drawing the subject, rather it’s permissible to say he is fixing onto the pictorial plane the concept and movement of the abstract point of view at the time his sight is grasping the motif provisionally using its concrete form. This provisional quality and fluidity in the way it questions the symbolic function of the painting and its surface are conventional, but it is even particularly a trend among contemporary, young Japanese painters.

As when you realize it’s an illusion when in Cezanne’s “Apples and Oranges” (circa 1899) the apples on the table end up appearing like pins holding down the tablecloth, there is a moment where we suddenly notice that Minamikawa’s “Beautiful Lady” (2006), too, is trying to sit at a strange angle. In the painting world these things are, perhaps, “noise” that pulls us back to reality. But no matter the work, neither the degree of completion nor the beauty is lost with these techniques. On the contrary, a form of expression of new space is presented―like the way noise music or cacophonous sounds have presented a fresh beauty in sound. The world as we experience it now is disconnected from us―a multi-layered and fragmented history. Therefore, Minamikawa, it is possible to perceive in a high-tech way a strong preference for the nature of a painting’s facade and the classic artistic practices of predecessors such as Monet and Cezanne, and like them when painting a picture, try to make a beautiful painting, too.

Susan Sontag in “An Argument about Beauty” (Daedalus Fall, 2002) explained the ridiculousness in the expression “interesting”, which has started to be used instead of “beautiful” and the importance of restoring beauty as the foundation of value judgments. Certainly we would not say “the sunset is interesting”. Precisely because they are works that are difficult to describe, in Minamikawa’s work there is a limitless potential for us once again to talk about beauty.

Shihoko Iida (Tokyo Opera City Art Gallery, Curator)